I just finished eating lunch with Rich Brown, a faculty member in UW-Madison's Department of Family Medicine and the speaker for today's Neuroscience and Public Policy (NPP) seminar, and I have a curious case of the warm fuzzies. I'll be seeing him talk at 4.

For the past 24 hours -- that is, since walking out of a discussion section on the last seminar in the series, delivered by UW Life Sciences professor and wunderkind Dietram Scheufele -- I've been preoccupied with dark and gloomy thoughts on the state of the American political system. Research done by Scheufele, his colleague Dominique Brossard, and others on science communication has revealed some depressing implications for how we think informed dialogue and debate should go in the U.S. Basically, that body of work has exposed shortfalls in the so-called "deficit model" of public engagement in science: the idea that if only people were more familiar with the facts and figures, if only they knew what we who study an issue know, they would see things as we do and shake themselves loose of deeply-entrenched ideological positions.

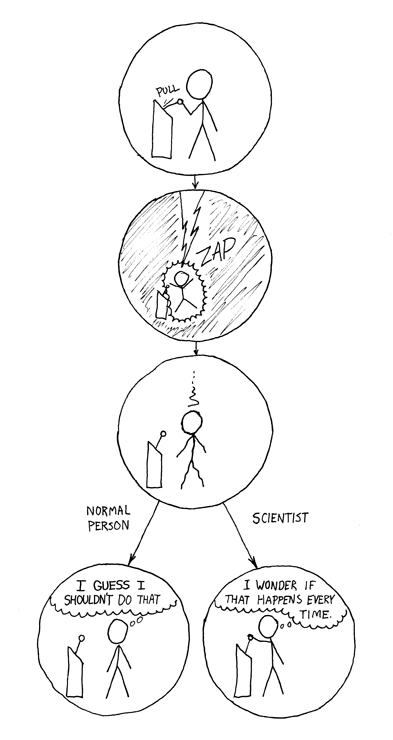

As it turns out, that's not true. At the best, we've overestimated the persuasiveness of scientists or the open-mindedness of Americans (not to mention the possibility of being wrong in the first place). At worst, all the people who listen to evidence have already joined the team, and the people who remain are recalcitrant or simply subscribe to a different view on how facts matter in determining what is right and good. The extent to which new information changes their opinions tends to decrease with increased ideology and religiosity, though I'm not interested in falling head-over-heels into an ad hominem attack. The point is, we can't just sit people down in a room, show them the graphs, make sure they understand, and send them on their way to building a brighter, more rational world. We have probably been arrogant all along to believe academia has (or deserves?) that kind of power, at least to the extent the findings hold up.

You may have also heard some hubbub about comment sections, especially in science reporting, and how flamers and trolls really do distort people's perceptions of the science so they walk away with the wrong ideas. Again, that was Scheufele and Brossard.

At the end of Scheufele's lecture a couple weeks ago, the cameraman recording the talk for online access piped up during the Q&A session, saying that of the hundreds of lectures he'd thus recorded, this one was the most depressing. If the evidence suggests that many people just don't listen to facts and reason after all, how the heck are we going to solve the increasingly American problem of policy and politics divorced from reality-based solutions?

Scheufele, cheery and charming though he is, only said that his work identified a problem rather than posing a solution... and furthermore, he apologetically grimaced, he might be wrong?

Don't worry, I'll get back to Rich Brown and my warm fuzzies. Hang in there, I want you to get there with me.

------------------

So yesterday's discussion section, concerned with Scheufele's talk, was a lightning round of political philosophy, legal analysis, and fruitless efforts to pin the cause of the problem on anything or anyone in particular. My friend in the Neuroscience and Law program, Joe Wszalek, quite defensibly felt there existed enough precedent and latitude in the framers' views on tyranny of majority to see our current gridlock as an unusually bad case of democratic flu, rather than the first symptoms of something more sinister. I adopted the view that, to extend the conclusions of Hacker and Piersson's Winner-Take-All Politics (also mentioned in my last post), our system is approaching the state of a "solved game" such as Connect 4, in which there exists an opening-move strategy that can never lose. I argued that in the current situation, that solution stems from the convergence of three things:

- The American political system is designed so intently to check power that it is much more disposed to resist radical change than it is to adopt it, especially over the protests of a minority. It thus takes a lot less political will to keep things as they are than it does to change them.

- Our electoral mechanisms ensure the survival of a two-party political system, in which gridlock is basically inevitable as party territory will forever shift to accommodate changes in political attitudes until it reaches a sort of Nash equilibrium. It's not coincidence that Presidential elections are routinely won 51-49.

- One party has as its primary policy agenda the simple preservation of the status quo.

If that party chooses to use the leverage afforded them by our inertia-favoring system to enact inertia, they will rarely have to work harder than the other party or expend more political capital to win every fight they enter. This blog is not a book, at least not yet, so I will not go into a very long discussion on the particulars of my position, though I encourage you to research more on your own with Hacker & Pierson, and their skeptics, as a jumping-off point.

Then yesterday evening, I read this article in Gawker which introduced into the memetic lexicon a new (or at least, revitalized) buzzword, smarm, whose insidious spectre looms large over the internet's other favorite accusation, snark. In it Tom Scocco argued that, for all the legitimacy of complaints against needless snark in criticism, smarm -- a form of bulls**t characterized by hollow calls for civility and indignance at pettiness -- is the deadlier disease, for it can never be well-intentioned. It is "cynicism in practice," not in attitude, says Scocco, and he has a point. We all hate political talking points, even as we all acknowledge that in the current paradigm they're an inevitable part of playing the game. I, more than most progressives I hang around, insist we musn't dehumanize politicians and instead should blame the perverse incentives of this great big Connect 4 game we keep playing, but it doesn't change the fact that campaigns are more about (metaphorically, and maybe literally) gauging whether the median voter prefers McDonald's or Burger King than about what policies will best help the poor even eat there.

I even ended up reiterating with my girlfriend a previous debate we'd had about the character of politicians, the extent to which we should hate the players or the game, and whether it was even possible to run a nationally-visible campaign for public office primarily on evidence-based policy platforms.

Finally, this morning while putzing around waiting to meet Brown for lunch, my NPP colleague Princess Ojiaku bumped into me, and we talked about the implications of Scheufele's work and our fears that all this was intractable, despite my convictions that Americans are smart, deserve the smartest policies and politicians in the world, and would gladly bring all of it about given the chance. Even a follow-up to the discussion from our program's advisor, noting that researchers were working on ways to expose social media users to new ideas while still taking their preferences into account in generating newsfeeds, seemed like a concession prize; a footnote.

I was genuinely worried, for the first time in a long time, that nothing I or anyone else could do would stand a chance of changing all that. Princess and I left the building (which is dedicated to public and industry research cooperation), crossed University Ave. (on the campus of a school dedicated to sifting and winnowing for the truth and putting that truth to work for its state), and without remembering any of that, trudged down the hall towards the conference room for lunch.

----------------------

Richard Brown is a very nice guy, in a way that is both stereotypical and specific. Not a generic, neighbor-cuppa-sugar nice, but an I-bet-you're-interesting nice. He asked us about our research interests, and then he told us about his while we ate sandwiches. He's primarily interested in promoting the use of screening for mental health and substance use issues as a means of entry to interventions, which his research, done in collaboration with the La Follette School's Dave Weimer, has found to be a very effective way of ensuring that people get care they don't realize they need. He also told us about his favorite thing in the world, I'd judge: a style of medical support called Motivational Interviewing (MI). I'd heard of it, but I wasn't as familiar with it as I was with better-known tools in the therapist's toolkit -- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, mindfulness therapy, etc. I remembered it had something to do with giving the patient more credit for their successes.

He explained that MI was a means of interacting with patients that focused on maintaining the patient's agency. Instead of hunting for poor health behavior, harping on potential adverse outcomes, and hammering the desired changes, MI is structured to help patients volunteer useful information, form discrete goals, and analyze their own health problems. In particular, it requires the clinician to be supportive, non-adversarial, and above all empathetic towards the patient. The doctor is there to be a guided sounding board, a source of information, and affirmatively supportive. Ultimately, the objective is to help patients resolve ambivalence, arrive at a goal, and then commit to the changes they need to make to reach that goal.

Here's why this is relevant. MI has been shown to be more effective than traditional clinical practice in a number of different settings since it was formulated in the early 80's by Miller & Rollnick. The man on whose work MI is based, Carl Rogers, developed the humanistic approach to psychological counseling, and was eventually nominated for a Nobel Peace Prize because of the applications of his methods to cross-cultural conflict resolution in places like South Africa and Northern Ireland.

In other words, MI represents the evolution of a rhetorical style whose central tenet is that perspective-taking and empathy are the keys to persuasion. Now, I've been lucky enough to study the mechanisms of empathy, and its role in psychopathy, in a terrific lab, and I've been treated to some of the most cutting-edge thinking in the academic world on the subject by collaborators. Empathy alone is not the only thing that separates most people from psychopaths, but it's a big part, and I freely admit it's an idea at the center of a lot of my personal pet theories. With that disclaimer out of the way, in my view MI provides a certain measure of validation for empathy as a fulcrum in facilitative social transactions. If it's true that the "deficit model" fails to predict the stubbornness of many Americans in the face of scientific evidence, the role of empathy in MI may explain what science communication lacks, and naturally suggest how we should change our approach.

If the "deficit model" were accurate, then any amount of accurate information a doctor provided a patient would cause the patient to behave in a more health-promoting way. The success of MI relative to a more confrontational approach indicates that's not the case. Similarly, whenever scientists or organizations antagonize people who seem to either lack or ignore evidence, perhaps they are unthinkingly making their own task harder. The distortion of understanding caused by vitriolic comment sections, which would seem to suggest there's power in the adversarial approach, could just as easily be interpreted as polarization in response to overzealous troll-hunting by defenders of science. If we really want to change people's minds, we cannot afford to frame science communication as an us-versus-them decision. Despite every temptation to do so, the evidence here seems to indicate that, at least at the mass level, and given the tools of social media we have at our disposal, the high road really is the only road. And in particular, starting with an understanding of where those we disagree with are coming from is an important technique for changing minds.

____________________

Here's the thing. Scocco's point in the Gawker article is that snark, while somewhat destructive, is at least honest, while smarm is disingenuous and amounts to misdirection in the pretended name of civility. Rhetoric is not a new field, nor is persuasion a new technique, and I realize that by choosing to focus on the work of a few current science policy experts I'm omitting literally millenia of thought on how to reach people who refuse to face the truth when it's available. But all I'm really trying to say is the following.

- Ideological debate often precludes the implementation of science-based policy.

- Freedom of religion and a commitment to independent thought make it unlikely science will simply overrun ideologues in the near future, when a lot of science-based policy would be most effective to implement.

- Studies predict that convincing religious and ideological people of scientific fact is next to impossible.

- But maybe we've just been doing it wrong, and doing it right means treating our ideological opponents with the respect we want for ourselves.

I know that extremists piss scientists off all the time. I know they even put people's lives in danger. I know they make town-hall meetings hair-raising experiences, and we've been trying to take the high road a long time. But if the contrast between internet flame wars and cooperative doctor-patient interactions provides any insight at all, it's that the fact that it's hard doesn't mean we can compromise on our good-faith efforts to do science outreach not just diplomatically, but empathetically.

That's where the warm fuzzies came from. Maybe the quest to build society around shared knowledge isn't as hopeless as we thought, and maybe all that cheesy stuff that gives you the warm fuzzies is a necessary part of the solution after all.