As anyone I know could tell you, I am a dog person. To an unhealthy extent.

|

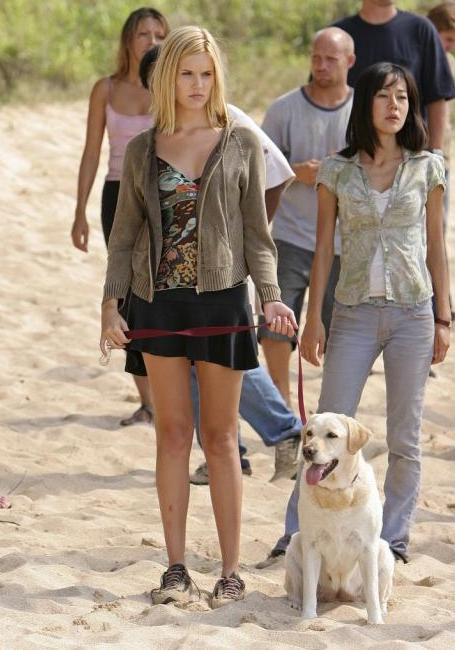

| Don't look, Vincent... via Lostpedia |

- The only time I cared about anyone in Lost was when the dog Vincent tried desperately -- and ultimately in vain -- to follow his human friend Dawson, who was leaving the island on a raft, into the ocean.

- If there is a dog at a party, I will begrudgingly leave it for a few minutes at a stretch to interact with my human friends. I would rather just lie on the floor with it, in whatever clothes I'm wearing, and pick up its vibe.

- I will also play with it until parts of my body stop working, and usually only when somebody points out that fact out of concern for my continued health.

So when I initially saw Berns' article, and the subject it broached, I was pleased! Yes, I say, let's consider the question of whether dogs are people. Personally, I think that's too simple a proposition to capture the truth, but we'll get to that.

The bottom line of my reaction is this: I appreciate what the article was trying to do -- and unlike a lot of scientists I know I don't say this next bit a lot, because popularizing science isn't always bad -- but I found it really inappropriate in tone, scope and scientific content.

The elements of neural activation Berns was citing basically correspond to evidence of pleasure, reward and motivation. (My friend Ryan, who works on animal behavior in rats, points out that regardless of what they actually can do, the dogs in question weren't demonstrating "love and attachment," they were demonstrating "preference.") The caudate, which is part of a structural assembly called the striatum, interfaces with some of the evolutionarily oldest structures in the mammalian brain. As per the experiments on drugs and rats in a recent post, these areas -- while varied in their exact purposes and connectivity profiles -- largely support the dopamine-powered "reward" circuit, technically called the mesocorticolimbic pathway. I'm not an expert on it, and I'm fuzzy on the caudate's specific role within the circuit, but Ryan agrees Berns' attribution to it of such nuanced emotions (much less personhood) is an overreach.

|

| Yes, it's swirly. Brains are weird. via Brainposts |

In a very crude sense this circuit is the reason we do anything -- without integrating a sense of motivation and anticipation of reward into our value judgments, we'd be so apathetic we wouldn't bother to eat, and we'd just die. It's also the circuit implicated in drug addiction, or for that matter, *anything* addiction. In many cases, the kinds of things that circuitry is responsible for are the impulses we actually need to fight to be considered persons, at least in the conventional moral sense. If you've heard the phrase "he was behaving like an animal," there's reason to believe the culprit was, colloquially speaking, letting his striatum drive the car unsupervised.

If anything, what we need to show dogs are people is indication of "higher" functions, or whatever you want to call them.

Side note: personally, I think the moral significance of living beings occurs on a sliding scale, where a goldfish registers and its well-being is worth something, but isn't equal to a person; and a dog is closer to people but generally comes up slightly short (though sometimes very slightly... and maybe there's some overlap, with dogs I'd choose to keep alive at somebody else's expense). Some other blog post I'll explain how I see this as consistent with Giulio Tononi's work on consciousness. Other scientists, including my one-time boss Julian Paul Keenan and his mentor Gordon Gallup, have considered the value of using self-consciousness (as determined by the ability to understand the significance of one's own reflection in a mirror) for one of the criteria of "personhood." The point is there are a lot of ways of approaching this problem, and few of them are simple, which stems from the simple fact that people are complex. (*snap*)

|

| Complexity. Deal with it. via WiffleGif |

Anyway... if we hypothetically bought Berns' reasoning, i.e. that evidence of comparable activation patterns in comparable cognitive paradigms is evidence of comparable function, and thus personhood (which can get a bit fishy), I argue we'd need a lot more and better benchmarks. We'd need dorsolateral prefrontal cortical activity, indicating self-control and abstract thinking. We'd need ventromedial prefrontal activity, and insula, maybe anterior cingulate -- or their homologues, anyway -- corresponding with complex emotional responses, especially social ones like guilt and empathy, being part of dogs' decision-making processes. After all, these are among the things people say separate us from animals.

|

| All four areas -- ventral striatum (VS), ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC), insula (INS), and anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) in one handy, murderous image. Front of head is to the right. via PLoS ONE, h/t Al Fin. |

But we probably shouldn't buy Berns' reasoning. That's because:

- If you're going to try to build homologues, most of the time mammalian brains -- which are, after all, like a series of iPod models with incremental improvements -- will roughly line up, so you'll have something to compare. It's really a question of how developed and interconnected those areas are. Or at least, we know it'll probably be a combination of tricky things.

- Dogs are generally going to be able to do, and show activation in, a lot of the simple tasks we use in humans, simply because making really sophisticated experimental designs to probe thinking and feeling is complicated. Neuroscientists and psychologists have to constantly refine and revise experiments to ask more and more specific questions.

- Dogs don't have parts of their brains that don't work. NOTHING does. Brains don't have areas that can't be made to "light up" under the right circumstances. If we did, those traits would be selected against in evolution, because we'd be burning calories with useless brain matter that we could've used for something else. (Next time somebody says we only use 10% of our brains, hit 'em with that.)

And just to wax advocate for a moment here, the sentence "by looking directly at their brains and bypassing the constraints of behaviorism..." makes Ryan, generally a very peaceful person, very inclined to violence. Without behavioral research, we wouldn't know (or continue to learn) about what makes animals AND people behave the way we do, and how our brains work that magic. Nobody is saying we should all think of people like Skinner thought of rats. The only thing imaging provides in this context is a more global perspective on neural activation patterns during that behavior. And I'm an imaging person saying that!

Look, lots of people criticize neuroimaging researchers for vastly overreaching in their claims based on relatively fuzzy, and difficult to interpret, imaging data, and this is a perfect example of that. So while I in large part agree with the premise of the article, I completely disagree with how Berns arrived at it, and how he depicted the science that brought him to that conclusion. I'm pretty disappointed with the article as a high-profile outreach on behalf of the science community.

Next time, maybe I won't have to be so ruff on him.

Yes, I'm here all week.

ReplyDeleteI am really enjoying reading your well written articles.

It looks like you spend a lot of effort and time on your blog.

JAVA Training in Chennai

Selenium Training in Chennai

Java classes in chennai

core Java training in chennai

Best Selenium Training Institute in Chennai

selenium Classes in chennai

Java Training in OMR

selenium training in anna nagar

It's very Refreshing to see all your points...Keep Up this work!!!

ReplyDeleteJava training in chennai | Java training in annanagar | Java training in omr | Java training in porur | Java training in tambaram | Java training in velachery

Axure RP Crack is best software that you can create wireframes, flowcharts, user journeys, mockups, idea boards, personas, and much more.Axure Download Free Full Version

ReplyDeleteThese long distance birthday messages will show him how much you care. ... jokes/funny birthday ideas/birthday message/long distance love quotes/how to make .Website

ReplyDelete