|

| Brain iz confusing place. ichcb, via flickr |

My friend Katherine called my attention to this fun little exercise: the brain represented as a subway map, as imagined by artist Miguel Andres and picked up by Know More, an offshoot of the Washington Post's much-loved Wonkblog. Unfortunately, I told her, I have to disavow it completely. (Sorry if you just spent 5 minutes memorizing it.) It's a darn cool idea, but it's not a teaching tool.

I'd say (somewhat generously) that it's about 30% right on anatomy, 20% on functional localization, and -- most damningly -- less than 10% right on how the brain actually works. It's more misleading than informative.

I don't know whether Andres ever hoped it would be used at a place like Wonkblog; it could have been just a creative work, by which standard it's cool enough. But since it was, and now it's going around the web, I'll try to 'splain what it does wrong.

Anatomically, it's a crapshoot. For one thing, it seems to say that analogous systems on opposite sides of the head are doing totally different things. This isn't true. Now granted, while the old "left brain vs right brain person" thing is deeply exaggerated, it's true that the two halves of the brain do subtly different, but coordinated, things. However, those processes are usually complimentary -- for instance, the area on the left that does language production, called Broca's area (hence the reference on the map), has an analog on the right that does pitch inflection, and other "non-verbal" communication stuff.

But then half the time, this map's routes are just totally unrelated to how the brain is actually set up. Not only don't your eyes go straight to different functions, input from your eyes goes ALL THE WAY TO THE BACK OF THE BRAIN, with a stop or two in the middle, to do visual processing. The image we reconstruct is then passed forward into the brain to do things like physical spatial awareness, object recognition, etc., and then further forward still to do things like emotional associations, decision-making, etc.

|

| Where this map will get you. Peter Ward, via geograph |

The biggest problem is that looking for a particular instantiation of something, like "aggression," isn't gonna get you anywhere. You want to look at "mood," or "social cognition"? Well we're still arguing about it, but at least we believe there are areas within networks that might underlie stuff like that. Pointing at a brain region and saying "aggression" is like looking at a computer motherboard, pointing at an area and going, "PDF." It's like what, no.

Also, doing a 2D brain anatomy lesson is hella hard, cuz... it's not a 2D organ. Imagine doing a subway map, only instead of stops being at intersections, they're at offices. ("The next stop is: Lexington and 53rd. And the 26th floor.") Not the easiest thing to stick on a poster or a t-shirt.

Disappointingly, scientists are often pretty bad at this kind of thing, surprise. Arguably the best free, lay-centered thing you can get on neuro right now is the Brain Facts book published by the Society for Neuroscience (SfN), a professional organization. But it's not exactly "multimedia," and BrainFacts.org in general is a great idea, but it doesn't seem to be a lot of centralized learning resources so much as a feed of relevant articles.

This little feature, on the other hand, is kind of fun and to the point -- but it's talking about the project neuro researchers are currently tackling, not delivering the latest approximation of their results in an intelligible or interesting way. And it also brings up kind of an interesting analogy -- Google Earth.

Google Earth is an official product, obviously, but the dorkier among us remember when it had alpha and beta stages, and a lot of that was available to the public. They release funky little plugins now and again, like last year when they made an ancient Rome map you could overlay over the modern-day area. And when we look at 3D Manhattan and the buildings are wonky and the textures don't load, we're slightly peeved but much more amused. We want to play. And play we did, to the point where Google collected a lot of feedback by farming their testing out to interested people.

Making something similar for the brain would be a great outcome for neuro in the next decade; it's just harder because a) scientists are more afraid of being wrong than app developers, and b) people know what Manhattan looks like without Google Earth. We can't really say the same for, you know, the left inferior parietal lobule. Plus, a road is pretty easy to interpret; the brain's function is way less obvious a consequence of its structure.

...

HOWEVER! A Google search revealed that we do kind of have something like this now! Much excite! It's called the BigBrain, and it was rolled out in June of this year thanks to folks at Research Centre Jülich and Heinrich Heine University Düsseldorf in Germany, and the esteemed Montreal Neurological Institute at McGill University in Montreal. I'm going to be playing with it a lot. As for the functional part -- you know, getting off the brain train at "social cognition," etc. -- we've got a ways to go. Thanks in part to the BRAIN Initiative, however, which I'll discuss in another post soon, we might be just years away.

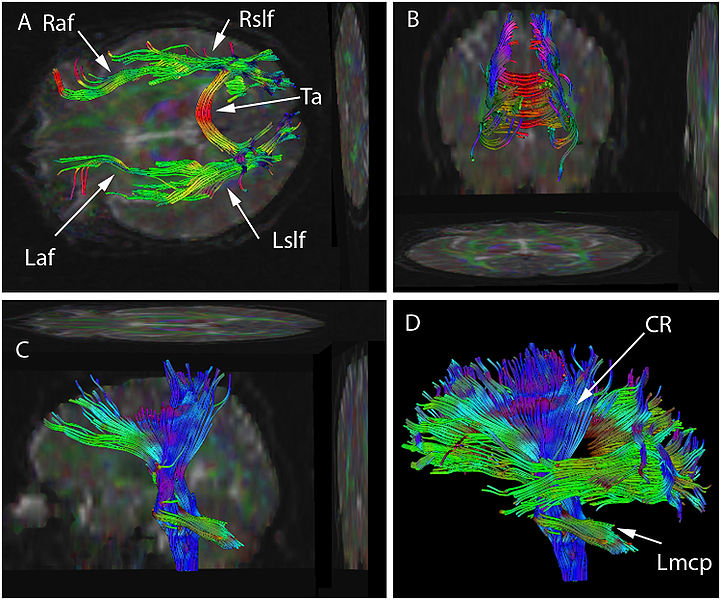

My only reservation is that a physical reconstruction, while hugely important and useful, isn't that interpretable a map (especially to non-neurogeeks). Cartographers, demographers, etc. are huge, lucky nerds because they get to fiddle around with how to present geographic information in the most novel and informative ways; to them, Diffusion Tensor Tractography is a map they'd want to delve into, whereas the BigBrain is more like satellite images of a mountain range -- nothing's highlighted for you. However, I'd bet the tractographic equivalent is right around the corner.

|

| Now THAT'S worth taking for a spin, amirite? AFiller via wikimedia |

No comments:

Post a Comment